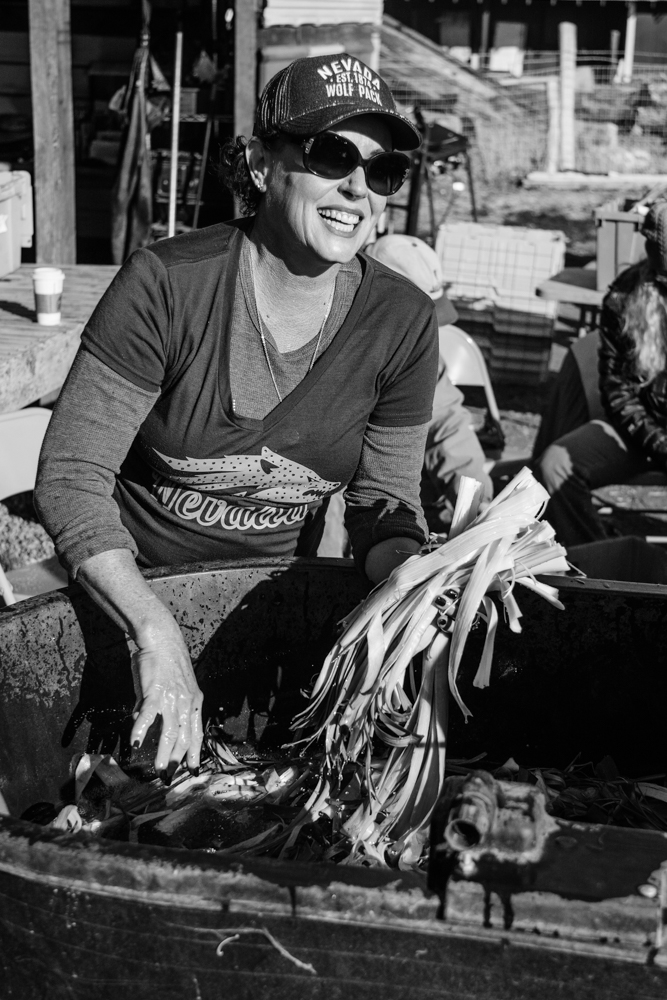

“You’ll never leave a Basque kitchen hungry,” says Marie Jausoro-Day, who helps tie sausages for Boise’s Mortzilla Dinner & Bazaar. Every fall, a group of Basques in Boise gathers at a nearby farm to harvest leeks; later on that week, they spend dozens of hours in the kitchen making the sausage–all the while, passing on ideas about what it means to be Basque.

The “Making Mortzilla” exhibit explores how the act of sausage-making preserves recipes, cultural traditions and a set of values among Basques in Boise, keeping up connections to a rural, agrarian culture in Idaho.

Presented in audio postcards and photo portraits, this project seeks to highlight the artistry of sausage-making and preserve reflections from sausage-makers, each of whom plays a unique role in producing this sausage for Basques in Boise and the wider community.

“Making Mortzilla” is produced by Olivia Weitz and Arlie Sommer, with funding support from the Boise City Department of Arts and History, and in collaboration with Euzkaldunak, Inc. and the Basque Museum & Cultural Center.

Olivia and Arlie would like to thank the Boise Basque community for sharing their stories and inviting us into their spaces. This project would not have been possible without the input of many, including Andrea Goyhenetche-Krueger, Jerry Aldape, Sean Aucutt, Marie Jausoro-Day, Ed Orbea, Martin Bilbao, Annie Gavica, Tyler Smith, Amanda Bielmann, John Bieter, Amy Fackler, Karen Ellis, and many others who took time to help with logistics, give advice, feedback, and context, and most of all to make the sausage. Thank you!

Click a name below to see and listen to Making Mortzilla. Audio by Olivia Weitz and photographs by Arlie Sommer.

We’re giving the leeks a nice little bath here making sure we have all of the sand out of them.

My name is Andrea Goyhenetche Krueger.

I’m out here in sunshine with friends and family and we’re getting our hands dirty, and we’re actually making a process; we’re processing food.

You don’t see any of this pretty bright green color in the finished product, but you taste it. They taste just like, you can taste the freshness of the leek when you bite into the mortzilla.

It’s about the community and remembering our elders and remembering our traditions and keeping them alive that I think it fills our hearts and then we can actually feed peoples bellies as well.

Put pam in the pot, this big square head cooking pan. We add pam. Add the leeks, add the onion, add the lard; leek, onion, lard and we cook it until we can feel the consistency of the onions and leek are soft enough.

My name is Jerry Aldape, I live in Boise, Idaho.

Probably ten or fifteen years ago when I was helping cook downstairs Ben Goitandia was the one who was in charge then. I’d watch how many leek containers he’d put into a cooking pot and how many onion he’d put in, how much parsley he’d put in, how much lard he’d put in. He’d use that ratio consistently until he got the mixture that he wanted. Then, he could tell while he was cooking whether or not it was the right ratio, so that’s how I learned it.

[Oven sound]

Maybe a little more. I’m tasting again the leek and the onions as they’re cooking to make sure there’s no crunch to ‘em. Even though they cook in that pot when we put ‘em in. We like to have these completely, fully cooked when we put them in. You can tell by tasting them.

There’s enough people who have cooked that if we were all gone they’d know how to cook it; they could tell when it was done. There’s enough knowledge out there that people could continue on if we were all gone.

When you’re mixing you want to reach deep down in the corners of this vat, this huge stainless steel vat. You’re up into your elbows of leeks and blood, and rice.

Mixing the blood sounds gross and everything and disgusting, but in the end you’re just mixing the innards of a sausage.

My name is Sean Aucutt, I live in Boise, Idaho.

[Basque] Probake ezazue. Probatu pixka bat.

[Translation] Try it out. Try a little bit.

I think that others have just sort of learned by watching as well. That’s the only way I’ve learned by, watching Benito do it for years and years and watching other people stir and taking turns actually stirring it so you know. You get a feel of what it needs to feel like.

So, it feels like a really dry rice pudding right now. Do you see those little bits and corners that we’re seeing that are green? That’s what we’re shooting for.

In my position, yes, I can have the final say, but I think that a lot of people know how to make it or a lot of people know the taste that they want. Not everybody agrees. I’ve just tried to keep the traditional recipe that I started with say 20 years ago, that Benny started and continued that tradition, and that recipe, and that flavor.

See how I keep bringing up more green. So, until we don’t see any more green that’s when it’s done. So until you reach that point, it’s not done.

If I didn’t have this activity or volunteering in my life or a part of this blood sausage making, I would really miss the camaraderie that I’ve grown to love with so many of the older Basque men and women as well. Because there’s such a great camaraderie and sort of feeling good about creating something from zero and then creating it for all of your members and for your community to love and eat; it’s super special.

My role in the mortzilla making is taking the lengths of the mortzillas that are tied off with the small string and looping them and tying them off with a larger string, so they can be rinsed and sent over to be cooked and then hung and dry.

[Basque language]

They are slippery and you have to get the knot through the under end of the loops of the length and then push the rest of the string through from the other side, so it’ll come up and knot by itself.

Now that I’m retired and I have the opportunity to come and work in the kitchen for mortzilla making, it’s something I feel, that not only the obligation to do, but it’s something I truly want to do, to be a part of, just like my folks were and their folks were over in the Basque country and here.

My name is Marie Jausoro Day, I live in Boise, Idaho.

[Oven door closing shut]

Being part of these traditions and keeping them alive is who we are within our culture and if it’s not the music and dancing it’s preparing the food and having people eat and taking part in the eating of that which you’ve prepared. It’s all part of that process. You’ll never walk away from a Basque kitchen hungry.

I am stirring the mixture on the stove to keep it from burning and scorching. Being cooked is the onions, the leeks and the parsley.

My name is Ed Orbea. I live in the city of Nampa.

[Stirring sound]

They’re getting there, looking good as you can see it’s starting to boil down. They take a full pan and probably reduces it by 50 percent getting all of the liquids out.

I’ve reconnected with friends through the dinner, and not only the dinner itself, but the preparation, you go out and you’re cutting the onions and leeks and you look across the table and there’s a second cousin or you go over to where they’re grinding everything and there’s two cousins and an aunt. All of a sudden “oh my god,” you know, and it’s hugs and kisses and all that kind stuff.

So right here we are chopping the onions right now. We’ll chop these until we have about 4 buckets full.

The onions all come in big large onion sacks and then there’s a group of people that sit around and peel all of the onions and then quarter the onions.

[Accordion playing]

One of the guys that comes out every year is my father. And so he’s out here right now. He’s done it for years. There’s at least a couple of days a year that we’re out making mortzillas together.

One thing that my father has taught me throughout growing up and you just see continued on throughout the mozilla making process whether it be out at the farm or at the Basque Center when we are actually stuffing and making the mortzillas is just hard work. He jumps right in no matter what project or task he’s supposed to be doing. He just goes in and does it until it’s complete and ready to be done.

My name is Martin Bilbao. I live in Boise, Idaho.