In 2021, Mullan, Idaho is a small, quiet settlement of about 700 people, but at its peak in 1940, 2,300 people, mostly miners and their families, called the bustling mining town of Mullan their home. Located just four miles west of the Montana border, Mullan was established in 1884 and was named after United States Army Captain John Mullan, who was sent to build a military road from Fort Benton, Montana to Walla Walla, Washington in 1850. The highest elevation of the road is seven miles outside of Mullan, at 5,168 ft.

In 1884 four men initially staked claims – Joseph Hunter, Frank Moore, George Goode, and C.C. Earle spent the winter of 1884 there looking for gold. Gold Hunter Mine and Morning Mine broke ground and the town of Mullan came to life between the two. It quickly became a welcome stop for pioneers heading west and a train stop with the arrival of the Northern Pacific railroad in 1889.

During Prohibition (Jan 1920-Dec 1933) Mullan was an important center for bootlegging, along the “Old Moonshine Trail” that brought Canadian whisky to thirsty Idahoans.

Many mines began closing in the 1950s, but the Lucky Friday Mine, operated by Hecla Mining Company, has been in operation since 1942 and with the completion of a #4 shaft project, expects another 20-30 years of mine life. Other mines are still in operation in the area today.

Reference: Larkin Mullin, “Mullan, Idaho,” Spokane Historical, accessed November 18, 2020. https://spokanehistorial.org/items/show/490.

The 1920 census reveals that Patrick Gleason, hotel manager, and Delia Billbery, proprietor, had immigrated from Ireland nearly thirty years earlier and together were operating a hotel on Earle Ave. South S. in Mullan, Idaho and had 61 boarders staying with them. Among the boarders were Juan Alvarez and Gregorio Fernandez who were identified as being from “Spain,” and working in the quartz mine in the census, but we do not know if they may have been Basque.

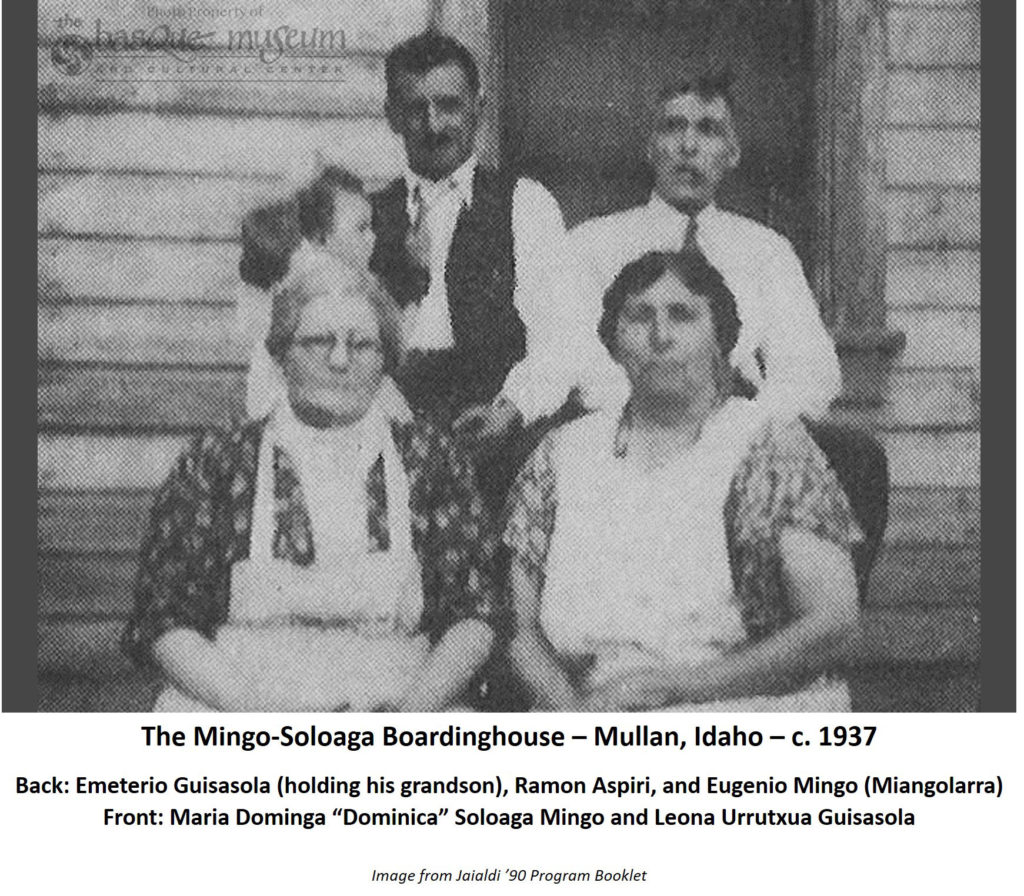

Some Basques did find jobs working in the gold, silver, and lead mining camps of this northern Idaho town and by 1925 a boardinghouse was established there by the Eugenio Mingo (Mingolarra) and Maria Dominga “Dominica” Soloaga Mingo (Mingolarra) family.

(To enlarge photos – Click on the image)

Eugenio Miangolarra, who later changed his surname to Mingo, had married Maria Dominga “Dominica” Soloaga in Gizaburuaga, Bizkaia and two of their children were born there – son, Ignacio, in 1908 and daughter, Marie, in 1909.

Eugenio came to Shoshone, Idaho in 1909 and entered into a partnership with Domingo Soloaga in a boardinghouse. Maria Dominga “Dominica” and their daughter, Marie, joined Eugenio in 1916 and Ignacio came in 1926. The family lived in Shoshone and Mountain Home, but moved to Mullan in 1925 and lived there until 1943. While Eugenio worked in the mines, Maria Dominga “Dominica” operated the sole Basque boardinghouse there from 1925-1939.

Basques were naturally drawn to their establishment where they could eat food they were used to from the homeland and communicate in Euskara, the Basque language, but the Mingos also had numerous Scandinavian boarders.  Four daughters were born to them in the U.S, Bene (Mingo) Schaffner, Virginia (Mingo) Shelley, Gloria (Mingo) Laborde, and Dolores (Mingo) Bianchini.

Four daughters were born to them in the U.S, Bene (Mingo) Schaffner, Virginia (Mingo) Shelley, Gloria (Mingo) Laborde, and Dolores (Mingo) Bianchini.

Eugenio retired in 1943 and the couple moved to Boise where they lived until their deaths.

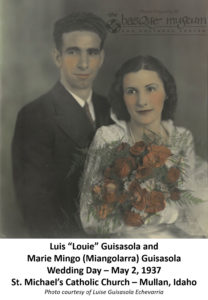

The boardinghouse building they operated at 126 Residence Street was destroyed by fire in the late 1940s. Their daughter, Marie (Mingo) Guisasola, continued the tradition and operated a Basque boardinghouse in Mullan at 108 Dewey Street from 1938-1943.

In 2015, the staff at the Wallace District Mining Museum prepared this map to indicate the location of various Basque boardinghouses that were in Mullan at various times.

.

Basques did not play a dominant role in the history of Mullan because their time here was relatively short and their numbers few, but census records provide some light on their story in this mining town. According to census records, more hailed from Finland, Norway, Sweden, Italy, Yugoslavia, Russia, Canada and from various states in the United States with only a few who were recorded as being of Basque decent.

The 1930 census indicates the following:

Other individuals listed as miners working in the lead mine were:

[Note – these single men could have likely been boarders at the Mingo-Soloaga boardinghouse].

The 1940 census indicates the following:

Marie (Mingo) Guisasola is listed as the head of the family with her two year old daughter, Luise, living with her.  Her husband had died suddenly the year before, shortly after the birth of her daughter. Marie’s strong work ethic allowed her to operate the business and succeed as a single parent.

Her husband had died suddenly the year before, shortly after the birth of her daughter. Marie’s strong work ethic allowed her to operate the business and succeed as a single parent.

The following people are listed as boarders living with her at the 108 Dewey Street location:

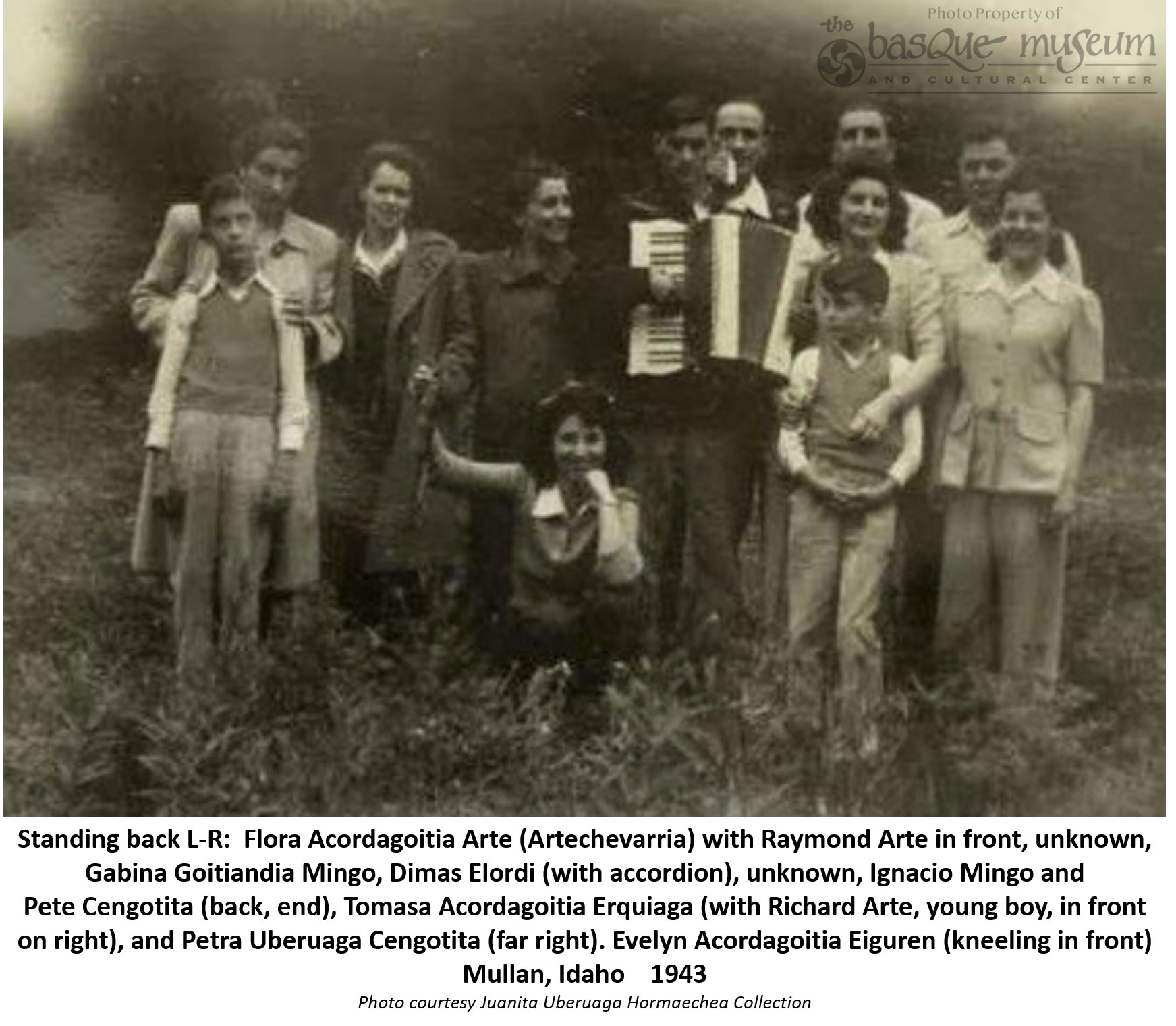

While living at his sister’s boardinghouse, Ignacio Mingo met his future wife, Gabina Goitiandia Mingo. Gabina graduated from Rupert High School in Rupert, Idaho in 1929, during the great depression. She went on to study at Albion State Normal in Albion, Idaho (near Burley, Idaho) and became an elementary school teacher. She taught in Nevada for three years as a country school teacher and then went to Mullan, Idaho to teach a 3rd grade class of about 30 children. She taught in Mullan for eight years and even had her future sister-in-law, Dolores (Mingo) Bianchini as a student. Gabina and two other women were living with a widowed, catholic woman from Ireland.  Gabina knew Ignacio Mingo’s family from their time in Mountain Home, Idaho, but met him in Mullan as he had immigrated from Gizaburuaga,Bizkaia after the rest of his family did at the age of twenty. Ignacio and Gabina married on July 1, 1943 in Shoshone, Idaho where Gabina’s sister, Gloria (Goitiandia) Gamboa was living.

Gabina knew Ignacio Mingo’s family from their time in Mountain Home, Idaho, but met him in Mullan as he had immigrated from Gizaburuaga,Bizkaia after the rest of his family did at the age of twenty. Ignacio and Gabina married on July 1, 1943 in Shoshone, Idaho where Gabina’s sister, Gloria (Goitiandia) Gamboa was living.

All of these boarders indicated that they had been living in Elmore County, Idaho in 1935….so they may have traded their sheepherding skills for those of miners.

Aspiri – We learn from Ramon “Ray” Aspiri, that his family lived in Mullan for a brief time while his father, Abraham Aspiri, tried his hand at mining.  Ray was born in 1936 and related a story that when he was 4 years old his father fell fifty feet down a mine shaft landing on an ore cart on the tracks below and breaking his back. Abraham spent six months in a body cast recovering from the accident.

Ray was born in 1936 and related a story that when he was 4 years old his father fell fifty feet down a mine shaft landing on an ore cart on the tracks below and breaking his back. Abraham spent six months in a body cast recovering from the accident.

Cengoitita – We learn from Teresa Cengotita Blaser, that her father, Pedro “Pete” Cengotita, was working in the mines in 1943 when he married Petra (Uberuaga) Cengotita on May 12, 1943 in Boise. Teresa was born a year later on May 13, 1944 and lived in Mullan for 2 years before the family moved to Boise.

Totorica – Teodoro “Ted” Totorica also went to Mullan in the 1940’s to try his hand at mining as he didn’t especially enjoy working with sheep in his father’s/brother’s sheep company. Mining wasn’t a good fit for him and he returned to southern Idaho after a short stint in Mullan.

Teresa Cengotita Blaser said that her father, Pete, and Ted Totorica, were good friends and did a lot of card playing in Mullan and then later at the Basque Center in Boise.

By 1943 both boardinghouses operated by Basques had closed. No significant presence of Basques remained in Mullan after that time.

Tape 2/side 1

0-14:30 Marie’s mother didn’t encourage her to pursue college, because she was needed at home; she finished her formal education at age 17. By the time Marie was married, her sisters were grown and some of them chose to go to college. Marie’s future husband, Louie Guisasola, came to work in the mines of (Mullan) 1936. His sister, Marie (Guisasola) Aspiri, and her husband, Abraham, and infant son, Ramon, also came to Mullan 1936. Marie Mingo met Luis “Louie” Guisasola at a Basque picnic in Boise, and he returned to call on her. They were married in May of 1937 in Mullan. Maria (Gabiola) Anduiza was a friend of Maria Dominga (Soloaga) Mingo’s and so Mingo family members stayed there when they went to Boise. When Marie was married, they had the party in the boardinghouse at Mullan, Idaho. After the marriage, the couple moved into Marie’s family’s boardinghouse and took it over, and her husband, Louie, worked in the mines again.

14:30-25:00 At the boardinghouse, Marie cooked mostly Basque food. The boarders paid twice a month, and always paid on time. In April of 1938, Marie lost her husband to gangrene after an appendectomy; their daughter was 8 weeks old. Marie kept the boardinghouse until 1943, when she moved to Boise where her sisters lived. She bought a house with one of her sisters and went to work at Albertson’s. She next worked at C.C. Anderson, a big store in town, but she hurt her shoulder, and so moved on to Boise Cascade.

Side 1

14:30-20:00 Ray’s father, Ramon Lotina, spoke English very well. He learned on his own and from other Basques who spoke English. He was very proud of his culture, but did not return to the Basque Country until he retired. He visited two or three times with his daughter, Carmen, staying for a month at a time. He retired from the mine in 1972 after working for years as a contract miner. Even though he loved the Basque Country, he enjoyed the United States because there was so much opportunity and the freedom to take advantage of it. By comparison, he felt somewhat oppressed and confined in his homeland. Ray talks about his father’s taxi service, which he owned for about a year before going to work in the mine.

Side 2

4:00-12:45 While working at the mine in northern Idaho, Ray’s father came down to Boise with one of his bosses to recruit Basques for the mine. They were unsuccessful in their efforts. There were only a handful of Basques working at the mines at the time, so there was not much of a draw for other Basques to come up and mine. In addition, there was no Basque club or organization at which they could socialize.

12:45-14:25 Ray does not remember his father ever having problems with discrimination. Most of the people his father worked with were also recent immigrants. Since they were all in a similar position they did not discriminate against each other.